Gazing Into the Borders: Guaman Poma and El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno

Gazing Into the Borders: Guaman Poma and El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno

abstract

Guaman Poma, the author of El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, documents Inka history and the consequences of Spanish conquest during the colonial era. The chronicle is composed primarily in Spanish with additions in Quechua, and is among the first works written by an Indigenous person about Indigenous people and of the conquest of Peru. The chronicle is among the first to identify and address archival practices of concealment and disappearance, manifesting as archival silences. It is a standout and standalone written record of Indigenous resistance during colonization, yet is missing from much of the historical record and most scholarship regarding Andean history prior to the 21st century. This article defines the context in which the chronicle was created, its provenance into the Royal Danish Library, the archival implications of its silence within it, and what justice might look like for such a text.

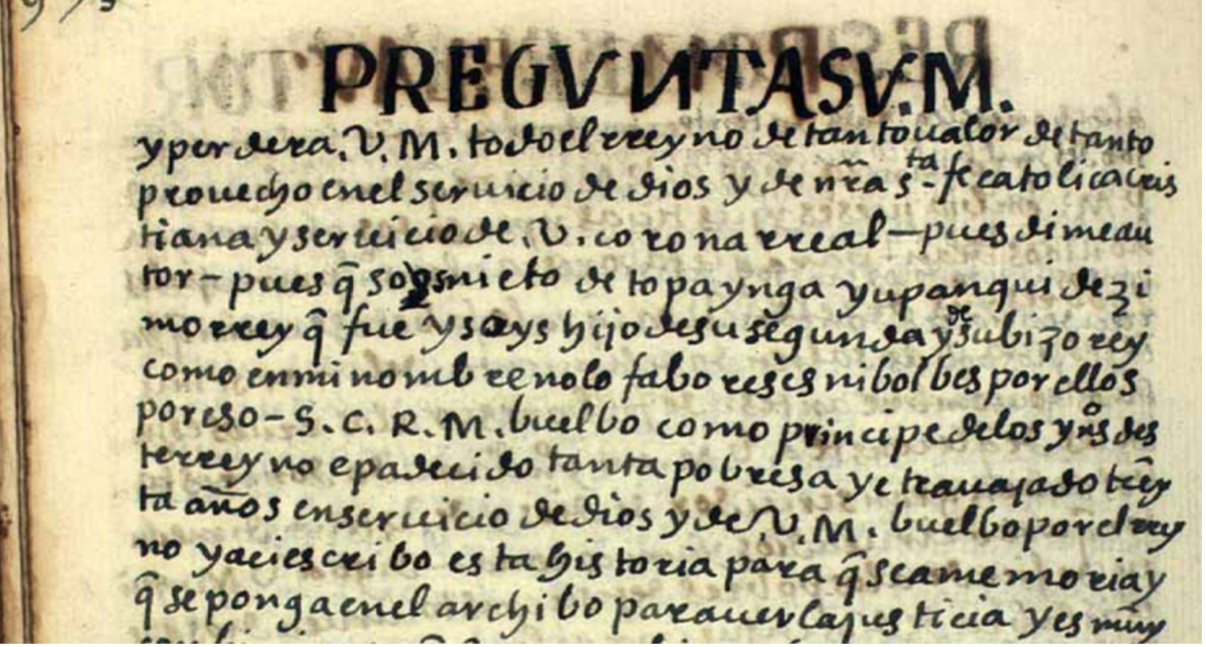

Figure 1: El Primer Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno (991). Courtesy of Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Copenhagen.

Figure 1: El Primer Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno (991). Courtesy of Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Copenhagen.

SCRM [Sacra Católica Real Magestad], buelbo como príncipe de los yndios deste rreyno. E padecido tanta pobresa y e trauajado treynta años en seruicio de Dios y de vuestra Magestad. Buelbo por el rreyno y ací escribo esta historia para que sea memoria y que se ponga en el archibo para ver la justicia.

SCRM [Sacred Catholic Royal Majesty], I return as prince of the Indians of this kingdom. I have suffered much poverty and have worked for thirty years in service of God and of your Majesty. I return to the kingdom, and here I write this history so that it is a memory and that it is placed in an archive to see justice.

Guaman Poma de Ayala, 1615 [translation, emphasis by author]

introduction

On February 14, 1615, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala writes a letter to King Phillip III of Spain from Lima, Peru, informing him that his chronicle had finally been completed and would soon be sent to Spain. Later, in the early months of 1616, Poma makes final amendments to the chronicle, including a chapter documenting his arduous journey from Andamarca to Lima (Guaman Poma de Ayala 1104). This journey would be the last Poma would take with the chronicle he had worked on for 30 years, and the chronicle’s journey, he wrote, would end at the royal office in Spain and later in an archive to serve as a memory, and importantly, to see justice. His chronicle is a history of the Inka empire before Spanish invasion, and a scathing critique of the colonial practices enforced in his territory. Poma addresses sections of the text to different readers as he delivers his critiques of them, but of utmost importance to him is King Phillip III of Spain, his Sacred Catholic Royal Majesty. His wishes and motivations made clear; he entrusted the viceregal government to help his chronicle reach its intended audience. It never would.

Since its completion, the chronicle has remained largely outside of archival documentation and colonial imaginations and exists mostly as a question in the minds of scholars. This is not only due to the context of the author and the work itself as an apparent contradiction in the colonial imagination, but also through the silencing of the work in archival record and literary canon for nearly 300 years. Poma exists as a necessary contradiction, outside the borders of colonial imaginary as an Indigenous author, a noble Indian, and a personification of fear. Poma’s work includes the then-unprecedented documentation of history in the Inka empire in Peru and the responses of an Indigenous person to Spanish conquest, historical creations that are still too often overlooked or unheard. Yet Poma’s work exists as a fringe history that has not been fully realized even 400 years after its creation. The chronicle would never be documented within a Spanish archive. Through a further examination of the archival record, the chronicle did make reappearances in memory, but for 300 years its existence, along with Poma’s, would largely be forgotten. Upon the chronicle’s academic “re-discovery” in 1908, and publication and translation efforts since 1938, scholars have worked to incorporate the text into their own imaginings of colonial philosophy, history, and critique. In this article I will explore the context of the chronicle and chronicler, its provenance into the Royal Danish Library, and the archival implications of its removal and disappearance from it. I will argue that Guaman Poma’s life, chronicle, and legacy are only understood while gazing into the borders of their context, pages, and history.

context of the chronicle and chronicler

Don Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala was born to a noble, senior cacique Indigenous family in what is known today as Ayacucho, Peru, shortly after its invasion and conquest by the Spanish empire. While his exact birth date is unknown, Poma attests to having had walked the earth for 80 years in 1615 (Guaman Poma de Ayala, 1096). With his noble lineage came access to formal education, and the opportunity to become fluent in Quechua, Aru, and Spanish. He later learned to write with the Latin alphabet. With this knowledge, Poma committed to chronicling the history of the Inka empire and the events of early conquest Peru. In 1615, Poma finished a manuscript he spent nearly half of his life creating. The work manifested in a 1189 page, multilingual and illustrated chronicle he named El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government). Composed primarily in Spanish with additions in Quechua, the work is among the first, if not the first, works written by an Indigenous person about Indigenous people and of the consequences of Spanish conquest during the colonial era. Ostensibly, it is also the first work with transcribed Quechua by a fluent speaker, adapted with the conventions of the Latin alphabet following Spanish phonology. Poma’s goal in writing the chronicle is twofold. First is to firmly plant the history of the Andean people, their beliefs, their traditions, and their lives into the historical record. Second is to name and attempt to amend his multiple grievances with the Spanish invasion and conquest of his home and people. This history, these grievances, and the audience for them are multiple.

The chronicle holds many histories in its nearly-1200 pages, and unfortunately, the scope of this article does not allow room for detail on its contents, though many scholars have done this work (see Adorno 2000, 2002, 2012; Bauer 2001; Olson & Casas 2015; Mamani Macedo 2016; Quespe-Agnoli 2018). For the purposes of this article, I will briefly describe the content itself. Broken into thirty-nine chapters, Poma documents precolonial life in the Andes – recanting traditions of idols, burials, festivals, and other traditions common under the Inka. Chapter 19 begins Poma’s extensive record and critique of the Spanish invasion of Peru, its subsequent dissolution of longstanding Indigenous traditions and cultures, and moral trespasses made against people in the colony. This section is a scathing critique of all levels of Spanish government, and is not shy in naming the responsible parties for the injustice he sees. His audience is made clear through multiple means but critically and initially by naming and addressing them directly within the text. Starting from the top down, he criticizes royal administrators, lieutenants, judges, notaries, administrators of the royal mines, royal overseers, caciques, and even the people themselves – including Spanish, criollo, African, Indigenous, and mestizo royal subjects.

Within each critique, he proposes some solutions to these injustices, at times resorting to pleading with the King to change his approach and relying heavily on a religious foundation. But Poma asserts repetitively throughout his text that for many moral trespasses, including deaths in the silver mines, the abuse of priests, and even his own failures in defending himself and his community, “no ay rremedio de todo esto [there is no remedy for all this]” (Poma de Ayala 526). This critical section ends at chapter 31, a chapter of religious and moral considerations for the King to reconsider the practices enacted in the colony. The chronicle thereafter includes chapters documenting the kingdom’s geography, earlier chronicles by other authors (including addressing his unique additions and departures from them), the author’s journey to Lima, and a chapter of the months of the year and their significance. Poma completes the chronicle with a table of contents and a conclusion for his work.

Inspired by, yet critical of chronicles of the past, in this text Poma employs literary modes that were common of the time, but not to Indigenous writers. The chronicle exists in direct conversation with the crónicos de indias, Relaciones geográficas de Indias, catecismos and sermonarios produced in Lima by criollo or Spanish authors with the express purpose to convert the Indigenous Andean population to Christianity. It is only in this context, Adorno suggests, that Guaman Poma’s chronicle makes sense (Adorno 2000, 65). In fact, he directly follows advice given to bridge the communication gap created by Spanish conquerors. In the preface to the Tercero catecismo, a document used with the goal to teach and preach the Indigenous populations of Peru, the first rule of rhetoric the writer suggests is as follows: Hase pues de acomodar en todo a la capacidad de los oyentes el que quisiere hacer fruto con sus sermons o raxonamientos He who wants sermons and reasonings to be fruitful must accommodate to the capacity of the listeners. (Catholic Church and Rosa y Bouret 1867, translation by author)

The language of the chronicle was important to Guaman Poma. Considering his extensive education in the ways of the Spanish, he knew that communication would only be possible if led with language that the audience could understand. In this case, it was not only writing in the language of Spanish, but in the literary modes that the Spanish created. Guaman Poma adhered to well-established Spanish literary modes of documentation in the Americas. Adorno remarks, “It is clear that, for this Andean, writing represented an attempt at social intervention in an environment where traditional models were no longer available” (Adorno 2012, 8). Guaman Poma knew the challenge he had set for him, used every intervention he knew of, and through this created one of the most important Indigenous texts of the time period.

provenance in the Royal Danish Library

El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno never made it to its intended audience, and perhaps has never been housed in an archive that would please Guaman Poma’s wishes. At least, the chronicle does not exist in the historical record of Spain. After its journey to Lima’s viceregal office, Guaman Poma’s chronicle disappears from the archival record for over 100 years. In 1729, the chronicle is identified for the first time outside of itself. It appears over 11,000 kilometers away from its origin, and over 2,000 kilometers from its destination, in the Royal Library’s archive in Copenhagen, Denmark. The Black Diamond, as the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen is often referred, sits facing the port of Copenhagen, built on the waterfront, steps away from the water where imports and exports regularly enter and leave Copenhagen. These steps, perhaps, are those that our Peruvian protagonist’s chronicle may have taken on its way to the archives of the Royal Danish Library. Unfortunately, its arrival here is bordered by decades, even centuries, of archival silence and removal. What follows in this section is a more contextual chronological timeline of the chronicle, curated by the work of librarians Richard Pietschmann and Harald Ilsøe, as quoted within the work of Adorno (2002, 16–23).

The first time the chronicle is identified in any archival record is in brief mention by an unknown archivist in 1729. The chronicle appears only as number 46 on a shelf-list for a miscellaneous assortment of manuscripts – including, among other records, “a dissertation on the kabbala, a work on political theory, a numismatics catalog, a verse-eulogy to King Frederick III of Denmark, an introduction to the Hebrew language, a work of Muslim history, a list of Ethiopian kings…”. While importantly standing as the definitive date that Guaman Poma enters the archive’s catalog, it is not classified appropriately, accurately, or at all. In 1786, the chronicle reappears in the Erichsen catalog. Jón Erichsen stood as the Director of the Royal Library from 1781 to 1787 and created the handwritten Catalogus manuscriptorum Bibliothecæ Regiæ scriptus et odinatus annis 1784-86. Here, in volume 3, on page 616, Guaman Poma reenters the page:

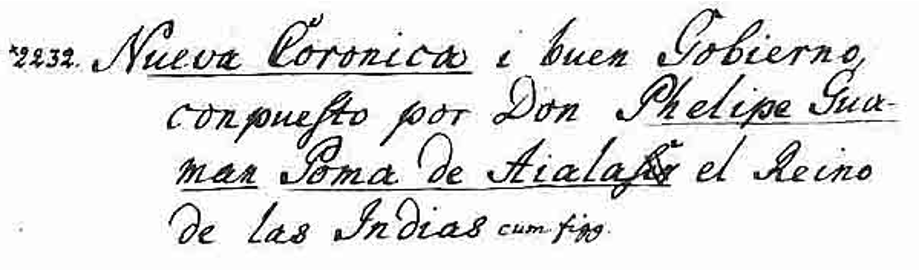

Figure 2: El Primer Nueva Coronica y buen Gobierno as it appears in the Erichsen Catalogue (1786)

Figure 2: El Primer Nueva Coronica y buen Gobierno as it appears in the Erichsen Catalogue (1786)

Guaman Poma is designated for the first time with a bona fide categorization by the Erichsen catalogue. It was subdivided into History, and then further classified into Recent History, then Spain. Also appearing in this subcategory is a text mentioned in the chronicle itself, by former viceroy Don Juan de Mendoza y Luna. His report, Luz de materias de Indias, is a report from the viceroy to his successor, documenting the errors in government largely in agreement with the injustices in Guaman Poma’s chronicle . The two works were so closely created that Rolena Adorno suggests that Mendoza y Luna’s report, along with Guaman Poma’s chronicle, may have been addressed to Spain in the very same diplomatic mail pouch (Adorno 2002, 93). Perhaps it was the limitations of Erichsen’s knowledge of Spanish to know that El nuevo corónica y buen gobierno, along with Luz de materias de Indias, is not appropriately categorized as Spanish history. While published in the language, the subject matter primarily concerns the Indigenous people of Peru, particularly their history and politics. Regardless, after the Erichsen catalogue, the chronicle again disappears from memory for 16 years.

Guaman Poma then makes additional appearances in the diary of August Hennings in 1802, and for the first time, is printed in official Royal Library reference in 1825 under the library director Erich Christian Werlauff . During his time as director, Werlauff also had the chronicle rebound. This is perhaps the first time since Guaman Poma wrote the chronicle that anyone had seen the entirety of its contents – more than 200 years after its creation. The chronicle then quickly returns to the border of archival record. Guaman Poma’s time in this border would last, again, for almost 100 years.

The final reappearance of Guaman Poma in the Royal Library of Copenhagen was in 1908 by Richard Pietschmann. Potentially amazed by his discovery, Pietschmann would then spend the next 30 years attempting to transcribe, publish, and publicize the chronicle. Poma’s chronicle left the Royal Library’s archive for the first time in 300 years and was taken with Pietschmann to Germany. A facsimile edition of the transcription was published in 1936, and for the first time, Guaman Poma was permanently implanted in public historical memory. It was later republished as a critical edition in 1980 by Siglo Veintiuno Editores. However, it is clear that even this version was soon enough for scholarly needs at the time, as a book published in 1993, Peru’s Indian peoples and the challenge of Spanish Conquest, notes that while Poma’s description of pre-Colombian and colonial life is “one of the most valuable indigenous sources available from colonial Peru… An important critical edition of his letter was published in Mexico in December 1980, too late to be consulted in the preparation of this book” (Stern 1993). With no fault to Stern, the inadequacy is clear in that Guaman Poma’s chronicle could not be included in an examination of the challenge of Spanish conquest 378 years after the chronicle was written and almost 60 years after its first publication.

complicating archival silences

Guaman Poma’s presence in the archive is one bookended by its removal from it. There is a plethora of extant dialogue in the archival theory canon that discusses and contextualizes silences. Not least of which was Michel-Rolph Trouillot pioneering research about archival silences that work to create and shift historical narratives. For Trouillot, histories are multiple; and so are their historicity (Trouillot 2015). In this framework, silences exist when there is a gap in the history being told, both in what is being documented and by whom. These silences are not easily defined nor identified; but they are unmistakable once found. Silences, as in the interpersonal sense, can indicate dismissal, exclusion, or purposeful retraction. Silences, as observed by Moss and Thomas, are only noticed if one goes looking for them (Moss and Thomas 2021, 11). Until they are found, they exist in a space of potentiality waiting to be addressed. Scholars have long discussed these silences and how they can enter the archive. In this section I work to complicate the kinds of silences that exist in the archive.

Every story cannot be told, much less preserved in an archive, and it is unrealistic to assume that they can be. With the rise of critical history and critical librarianship, it is ever more critical to recognize the gaps that exist in the historical canon. But archivists and historians alike have to face the unavoidable reality of silences. As Bradley suggests, silence is an exercise of power that subjects actors in history to neither life nor death; instead, silence reduces people to a state where it is as if they never existed (Bradley 2019). At times, silencing is a destructive practice, whereby governments, agencies, or systems otherwise holding a position of power restrict, destroy, or remove access to documents that may incriminate or implicate them in moral or legal wrongdoing. These are particularly present in colonial and dictatorial regimes, where the identification of crime could lead to national, international, or public response. However, this is not always the case. Other silences in the archive are created from gaps in documentation at the time of an event or biases in archivists’ decisions to keep or destroy records. As Trouillot observes, “What we are observing here is archival power at its strongest, the power to define what and what is not a serious object of research and therefore of mention” (2015, 99). In this way, it is not fair to characterize or address these kinds of silences in the same way.

These kinds of silences serve different purposes and powers, and are enacted in different ways. To this end, I propose a framework of defining silences in two ways by their methods of concealment or disappearance. Concealment silences are a result of records hidden or destroyed because of the contents they hold and their potential effect on understandings of history. By contrast, disappeared records create silence because of the philosophy of those who create and maintain records. To be disappeared is to be deemed unknowable, unimportant, or unacceptable in the historical canon. This imposed unimportance in the archive leaves some histories disappeared rather than concealed. Importantly, both practices of concealment and disappearances are active practices. Concealment is easily identifiable as active through power, politics, and control. Disappearing also involves an active practice of choosing, consciously or unconsciously, which histories are worth recording and preserving. Both involve the preemptive or retroactive nullification of people in the historical canon.

It is helpful to complicate silences in these ways to understand Guaman Poma’s positioning as a silenced actor in history. Poma, and his chronicle, cannot be defined clearly into the categorizations I have set. He is, at some points in his archival provenance, disappeared or concealed; at others, perhaps somewhere in between or neither. Whether concealed or disappeared, there is an active role in recognizing, documenting, describing, or publicizing the records that are silenced. However, the inactivity in the provenance of the text subjects Poma to a different kind of silence. Poma was not disappeared – in fact, he was active in ensuring that the history he documented was thorough and complete. Poma was also not concealed, at least in the same way that records previously discussed have been concealed purposefully to mold narratives of history. He was not removed from history as an active practice; yet the inactivity towards his text silenced him. Guaman Poma, and his chronicle, exist as a standout case where these practices of concealment and disappearance were identified and addressed by the author himself.

Poma’s unprecedented documentation of precolonial Andean history, his critique of the concealment of the trespasses against his community are the clear reasonings for the creation of the chronicle. It is relevant to revisit to the wishes expressed by Poma on 991: “SCRM… here I write this history so that it is a memory and that it is placed in an archive to see justice” (1615). In writing this, Poma recognizes the silence in the historical record of the histories he documents. This is clear in his identification of his audience – the Spanish crown, the one entity Poma believed could enact change; in his identification of where and how the text should be ultimately preserved – an archive in Spain; and in his identification of its purpose – that it is a memory, and to see justice. The very motivations for Poma to write his chronicle are an act against the same silencing practices that I have identified here. In the rising sea of literature about archival silences, Poma may have indeed been the first to actively identify and work to address silences.

This perhaps makes his own silence even more nefarious and tragic. Poma was neither concealed nor disappeared. There was little substantial active practice in committing or removing Poma from any historical canon, despite its presence. The inactivity towards the text is still a silence as it commits Poma to a similar state of nonbeing. El nueva corónica y buen gobierno exists in the temporospatial area between disappearance and concealment. Poma and his monumental text, in direct contrast to his utmost desire to be in memory, were merely forgotten.

seeing justice

For many silences, the assumption is that recommitting or recreating histories in the archival record is a way to address their injustice. For histories that are concealed, removing the explicit inaccess that various powers enact on documents detailing acts that could problematize their history and create viable critique of their actions could be a response. However, as Moss and Thomas describe, the ending of silences does not always resolve issues. They emphasize that the power of archives to prevent tragedies or to heal in highly conflicted situations is limited (Moss and Thomas 2021). Their examination of the release of documents regarding Korean “Comfort Women” during Japanese occupation of Korea, Taiwan, China, the Phillippines, and other territories during WWII found that documents confirming their existence did not bring peace or closure to the affected women and their families. The records documenting the abuses, which had been either destroyed or concealed by the Japanese government, were found in 1992, but the response to the documents and the justice they were able to bring about was incredibly limited. The Japanese government offered little more than an apology to the women and their families (Moss and Thomas 2021, 15). The case demonstrates the political invention, intentions, and exercise of creating and maintaining archives along with the limits that are created for concealed histories to see justice. Alternatively, histories that are disappeared may be addressed by the creation of new records that expand the historical canon around which they were created. For Moss and Thomas, this rigorous practice involves the critical reading of archival sources to extract as much information from a limited dataset as possible (Moss and Thomas 2021, 229). Using this framework, scholars have reconstructed narratives of enslaved women in the Americas and the Caribbean, bringing new light and importance to the tragedy and resilience of their lives (Hartman 2008; Fuentes 2016). This practice has also expanded to examinations of colonial juridical records and legal documents to examine precolonial and colonial Latin American queer identities and expressions (Tortorici and Marshall 2022). But these creations are not necessarily justice for their subjects. It is a reckoning with power and a shift in historical canon, but does not change the conditions where their subjugation in life or in the archive was acceptable. Hartman’s reconstruction of Venus in Two Acts specifically contends with the impossibility of a young enslaved girl’s story, personhood, and existence (Hartman 2008). Additionally, the piece serves as a testament to the failure of the archive. The underlying presence of Venus in the archive and the narrative crafted by Hartman recognizes her humanity and the violence of the archive. It is a form of justice for Venus to be known more than a dead girl in colonial record, but materializing her in this way does not undo the violence enacted upon her in life or in the archival record.

Similarly, the amount of justice Poma can be given for having been forgotten is limited in the archival setting. In 1997, the Royal Library released a statement including that “due to the delicate physical condition of this unique historical document and the need for its preservation, any kind of use or display [of Poma’s chronicle] is prohibited” (Royal Library of Denmark 2001, “About the Project”). Guaman Poma was close, again, to subjugation to remaining untouched, outside of memory, for an indefinite amount of time. However, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno exists today free to access online and optimistically immortalized on the Guaman Poma website (Royal Library of Denmark 2001). This act challenges in some way the inactivity of the text for the majority of its existence. The website was opened with worldwide collaboration in 2001 and provides high-quality scans and transcriptions of each of the 1189 pages.

But is this justice? Though he had no concept of what digitization could have meant, this approach assumes that the chronicle’s newfound accessibility may be justice for the its history of silence. Digitization does commit Poma to memory, but does not provide justice as Poma expressed. His chronicle was never read by King Phillip III, his concerns never addressed, and his desires for its protection within a Spanish archive were never materialized. For this, there is no remedy. Within Guaman Poma’s imagination for how his chronicle was meant to see justice, it can never be served. However, while it wasn’t read by the king, it can now be read by anyone with an internet connection and a working knowledge of written Spanish, if not a decent translation engine. While it does not exist physically in Spain, Guaman Poma is metaphysically present anywhere in the world. Because of this, he is undoubtedly entered into historical memory with more scholarship continuously being conducted with the text. While his manuscript was not historically treated with justice, the silence to which it was subjected, at least for the time being, has ended. Justice may not be possible for this chronicle, but its existence helps to complicate and expand histories in ways that are even more accessible.

gazing into the borders

With archival documentation and a framework of silencing, we can gaze into the borders that complicate Guaman Poma’s chronicle, silence, and basic personhood and look for answers that may never appear. As he existed, Guaman Poma was a contradiction. Guaman Poma asserted on the very first page of the chronicle that he was “el reino de las indias,” King of the Indians. He was a noble Indian, an Indigenous writer, consistently treading the borderlands between insider and outsider. His claims to multiple in-memberships are enacted by coronating himself to the Indians in the language of the conqueror. He intervened his subjugation in terms made familiar to him by Spanish conquest by directly dialoguing through European literary modes. Poma unprecedently used the confines of a colonial writing system to both engrain himself within and critique colonial traditions. In doing so, he accommodates for his audience’s limitations; he created his chronicle in a context expressly so that it would be understood by those who could not or would not understand his existence. However, this practice also identifies Guaman Poma as a threat or a personification of fear in colonial imaginations. He was identified as Indio ladino by colonial powers because of his literacy in the Spanish language. In his own parlance: Que los dichos corregidores y padres y comenderos quieren muy mal a los yndios ladinos que sauen leer y escriuir, y más ci sauen hazer peticiones, porque no le pida en la rrecidencia de todo los agrauios y males y daños. Y ci puede, le destierra del dicho pueblo en este rreyno. (497)

The corregidores, padres, and encomenderos despise the ladino Indians who know how to read and write especially if they know how to draw up petitions, because they fear these Indians will demand audits of all the injuries, harms, and damages they have caused. If they can, they banish these Indians from their pueblos in this kingdom. [translation by Frye 2006, 169]

Here, Poma’s oppositional and unacceptable existence pushes him spatially to the borders of the kingdom he reigns. It also pushes him metaphysically to the border of colonial imagination and perhaps it is the same attitude of unacceptability that pushed his chronicle to the silent borders of the archive.

What is clear through the archival record of El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno is that when Poma’s chronicle was pulled from the borders and archivists interfaced with the text, they couldn’t understand it. Evidently, for most of its existence in the archive, the chronicle sat in a box or on a shelf, untouched. Rolena Adorno remarks, “The absence of any owners’ marks or readers’ annotations on the manuscript, as well as its overall perfect state of conservation, likewise support its early deposit and withdrawal from hand-to-hand circulation” (Adorno 2002, 23). When it was retrieved, the chronicle likely passed through multiple rooms and hands that could not understand its context, language, or significance. This is evidenced further through the lack of classification in 1729, and misclassification of the text as Spanish literature in 1786. I would contend that the history of at-best misclassification, at-worst imposed miscellany of the text was not even the worst of its treatment in the archival record. It is the decades and centuries of silence that Poma was forgotten in that is its greatest tragedy. The archive’s commitment of Poma to nonmemory nullified his personhood, chronicle, and intentions. It committed him and his history to a state of nonexistence, and of never having existed. I propose this as the greatest tragedy because it is one that the author explicitly wanted to avoid. Gazing into the borders is a way to understand Poma as subject, actor, and creator of history. It is indeed the only way to understand Poma. The multiplicity of his apparent contradictions is what could have led to his silence in the archive and removal from the historical canon. One must gaze into the borders of colonial imaginations to understand his personhood and chronicle. Similarly, one must gaze into the borders of the archival record to understand his loss. I propose that Poma did not receive justice – not only did King Phillip III not read his work, but no one did for most of its existence. Not only was the chronicle not preserved in memory, in an archive in Spain, but was forgotten in the historical record. And for this, there is no remedy.

Historical scholarly understandings and archival records of El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno are limited by their borders. They impose categories and singularity that are incompatible with understanding anything outside or in between them. And this lack of understanding is what committed Poma and his chronicle to nonmemory for so long. Guaman Poma remains as a personification of fear today, particularly for historians and archivists. His work is so encompassing that it cannot be contained in one description, series, or collection. It fits under multiple categories, like the author himself. His work cannot be reduced to a simple history of the Indians of South America, an explanation of Manners and Customs, or a critique of Spanish colonialism. He is not easily understood or classified. His memory requires scholars to revisit what is known about pre-colonial Andean life and Spanish Colonization, and archivists to revisit the classification, preserving, and stewardship of the work of Indigenous people. Adorno encourages us to think of Guaman Poma’s text as a witness unto itself (2002). This is agreeable because for much of its history, the text remained its only witness. Though we can never know exactly what happened to the text, how it ended up where it did, or why it was forgotten, we do know now that it does exist. The chronicle is difficult to conceptualize due to its scope, material, and perspective. Guaman Poma himself existed within borders of colonial imagination. He even inhabited a border time, not pre-colonial nor post-colonial, but on the border of both. Poma’s truth exists somewhere within the border. Perhaps there is no remedy for the historical mistreatment of Poma and his chronicle. By gazing into the border, I hope to encourage the expansion of them. Critiquing assumptions about history, who actors in history are, and what they can be, is work with a long pathway ahead. But it is required work so that the kinds of injustices faced by Guaman Poma through the archive are committed to memory. Guaman Poma as an actor in and documentarian of history requires scholars and archivists to expand the borders of archival documentation and silences, as well as precolonial and colonial understandings of personhood, identity, and relationality. Poma’s historical journey is at once a tragedy and a reminder that he is not the only one who has faced this injustice. He is perhaps an encouraging reminder for those that work and exist in these borders, silences, and contradictions in the historical canon that there may one day be justice.